Relapsed Myeloma Treatment: Insights and Options for 2025

When a blood cancer returns after a period of remission, treatment decisions can feel more complex than at diagnosis. In the United States, relapsed or refractory disease is often managed with combinations of established drugs and newer immunotherapy approaches, guided by prior response, side effects, and risk markers.

A relapse can look different from one person to another: a slow biochemical rise in markers, a symptomatic progression, or a more treatment-resistant (refractory) pattern. In 2025, care in oncology and hematology increasingly emphasizes matching therapy to what has already been used, how deep the last remission was, and which toxicities accumulated over time.

This article is for informational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. Please consult a qualified healthcare professional for personalized guidance and treatment.

Relapse, refractory disease, and progression

Clinicians generally describe relapse as the return of measurable disease after a period of remission, while refractory disease means the cancer is not responding to a given therapy or stops responding quickly. Progression can be biochemical (worsening lab markers) or clinical (new symptoms such as bone pain, infections, anemia, or kidney dysfunction). The distinction matters because it influences how urgently treatment needs to change and whether a prior regimen can be reused.

Practical decision points often include how long the previous response lasted, whether the relapse happened on maintenance therapy, and whether the disease relapsed while actively receiving a drug class (for example, an immunomodulatory drug or proteasome inhibitor). A relapse that occurs soon after therapy may require switching to different mechanisms of action, while a longer remission sometimes allows reconsideration of previously effective options.

Biomarkers, genetics, and cytogenetics

Risk assessment in relapsed settings often goes beyond standard labs. Biomarkers such as light chains, M-protein trends, LDH, and imaging findings help measure disease activity, but genetics and cytogenetics help estimate risk and guide strategy. Common cytogenetic findings (identified by FISH or other methods) can include high-risk features such as del(17p), t(4;14), t(14;16), and 1q gains, which may shape the intensity and sequencing of therapy.

Genetics can also open the door to targeted approaches in selected cases. For example, venetoclax has been studied most notably in patients with t(11;14), though its use and combination choices are individualized and may depend on clinician judgment, safety considerations, and evolving evidence. Re-testing at relapse is sometimes considered because clonal changes can occur over time, and the biology at relapse may not match the original diagnosis.

Immunotherapy options and combination therapy

Immunotherapy has become a central pillar in relapsed care, often combined with other agents. Antibody-based approaches may include anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies (commonly used in various lines of therapy) and newer modalities such as bispecific antibodies and cellular therapies (for eligible patients). In practice, immunotherapy selection is influenced by prior exposure (for instance, whether an anti-CD38 antibody was already used), the need for rapid disease control, infection risk, and access to specialized monitoring.

Combination therapy remains common because it can deepen response and delay progression, but it also raises questions about cumulative toxicity. Decisions often balance convenience (oral vs infusion schedules), patient comorbidities, and the practicalities of monitoring (for example, infection surveillance or lab frequency). In 2025, many regimens in refractory disease aim to use a new immune-based mechanism while minimizing overlap with side effects from prior therapies.

Chemotherapy, steroids, and managing toxicity

While chemotherapy is not always the centerpiece of modern relapse regimens, it still has a role, especially when rapid cytoreduction is needed or when the disease is resistant to multiple novel agents. Steroids (often dexamethasone) remain a frequent backbone across many combinations because they can enhance anti-cancer effect and reduce inflammation-related symptoms, but long-term steroid exposure can worsen mood, sleep, blood sugar, muscle weakness, and infection risk.

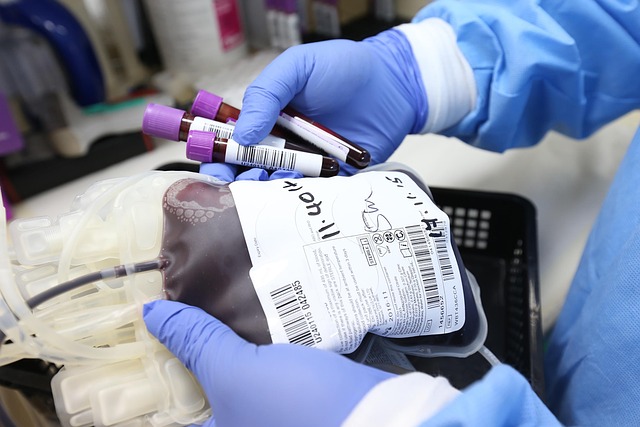

Toxicity management is often what makes a regimen sustainable. Neuropathy can limit agents associated with nerve damage and may require dose modifications or switching drug classes. Anemia may need evaluation for marrow involvement, nutritional issues, hemolysis, or kidney-related erythropoietin deficiency; supportive measures can include transfusion strategies or growth factors in selected situations. Kidney impairment can be part of the disease process or treatment-related, and it influences dosing, hydration planning, and supportive medications.

Finding specialized care in your area

For relapsed or refractory disease, many patients benefit from evaluation at centers with deep hematology expertise, access to advanced immunotherapy programs, and clinical trial infrastructure. The following organizations are widely known in the United States for hematologic cancer care; services vary by campus and patient eligibility.

| Provider Name | Services Offered | Key Features/Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Mayo Clinic | Multidisciplinary hematology care, transplant programs | Coordinated specialty evaluation; multiple U.S. campuses |

| MD Anderson Cancer Center | Hematologic oncology, cellular therapy programs | Large dedicated cancer center; extensive supportive services |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center | Hematology, clinical trials, cellular therapy | High trial volume; subspecialty disease teams |

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute | Hematology, transplant, trial access | Academic center model; integrated research programs |

| Cleveland Clinic | Hematology/oncology, transplant services | Large health system with specialty referral pathways |

| University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Health | Hematology, cellular therapy, trials | Academic medical center with specialty programs |

| City of Hope | Transplant and cellular therapy, supportive care | Focus on hematologic malignancies and complex cases |

Transplant, trials, and what “approval” means in 2025

A transplant strategy may still be relevant after relapse. Some patients who previously had an autologous transplant may be considered for a second transplant depending on the duration of prior remission, fitness, and available alternatives. Cellular therapies and other advanced immunotherapy options may require referral to specialized centers, careful infection prevention planning, and structured follow-up.

Clinical trials remain a major pathway for accessing emerging approaches, including next-generation bispecific antibodies, CAR T-cell refinements, antibody-drug conjugates under study, and novel combination strategies designed to overcome refractory biology. When discussing an “approval,” it helps to ask what line of therapy it applies to, what prior treatments are required, and what safety monitoring is mandated (for example, infection prophylaxis or neurologic observation). Even with approved options, eligibility criteria and practical considerations—such as travel, caregiver support, and monitoring intensity—can strongly influence real-world feasibility.

Relapsed disease management in 2025 is increasingly personalized: risk markers, prior therapies, remission duration, organ function (including kidney health), and side-effect history such as neuropathy or anemia all shape the plan. The most durable approach is often the one that is both biologically appropriate and tolerable enough to stay on long enough to control progression while preserving quality of life.